Violent video games linked to child aggression

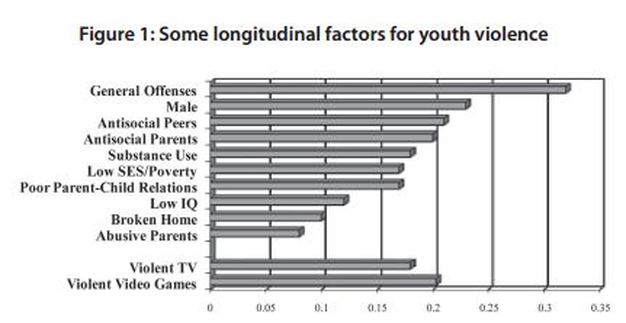

percentage of population

About 90 percent of U.S. kids ages 8 to 16 play video games, and they spend about 13 hours a week doing so (more if you're a boy). Now a new study suggests virtual violence in these games may make kids more aggressive in real life.

Kids shouldn't play games where hunting down and killing people is the goal, says one expert.

Kids in both the U.S. and Japan who reported playing lots of violent video games had more aggressive behavior months later than their peers who did not, according to the study, which appears in the November issue of the journal Pediatrics.

The researchers specifically tried to get to the root of the chicken-or-egg problem -- do children become more aggressive after playing video games or are aggressive kids more attracted to violent videos?

It's a murky -- and controversial -- issue. Many studies have linked violence in TV shows and video games to violent behavior. But when states have tried to keep under-18 kids from playing games rated "M" for mature, the proposed restrictions have often been challenged successfully in court.

In the new study, Dr. Craig A. Anderson, Ph.D., of Iowa State University in Ames, and his colleagues looked at how children and teen's video game habits at one time point related to their behavior three to six months later.

The study included three groups of kids: 181 Japanese students ages 12 to 15; 1,050 Japanese students aged 13 to 18; and 364 U.S. kids ages 9 to 12.

The U.S. children listed their three favorite games and how often they played them. In the younger Japanese group, the researchers looked at how often the children played five different violent video game genres (fighting action, shooting, adventure, among others); in the older group they gauged the violence in the kids' favorite game genres and the time they spent playing them each week.

Japanese children rated their own behavior in terms of physical aggression, such as hitting, kicking or getting into fights with other kids; the U.S. children rated themselves too, but the researchers took into account reports from their peers and teachers as well.

In every group, children who were exposed to more video game violence did become more aggressive over time than their peers who had less exposure. This was true even after the researchers took into account how aggressive the children were at the beginning of the study -- a strong predictor of future bad behavior.

The findings are "pretty good evidence" that violent video games do indeed cause aggressive behavior, says Dr. L. Rowell Huesmann, director of the Research Center for Group Dynamics at the University of Michigan's Institute for Social Research in Ann Arbor.

There are two ways violent media can spur people to violent actions, said Huesmann, who has been studying violence in media and behavior for more than 30 years.

First is imitation; children who watch violence in the media can internalize the message that the world is a hostile place, he explains, and that acting aggressively is an OK way to deal with it.

Also, he says, kids can become desensitized to violence. "When you're exposed to violence day in and day out, it loses its emotional impact on you," Huesmann said. "Once you're emotionally numb to violence, it's much easier to engage in violence."

But Dr. Cheryl K. Olson, co-director of the Center for Mental Health and the Media at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, isn't convinced.

"It's not the violence per se that's the problem, it's the context and goals of the violence," said Olson, citing past research on TV violence and behavior.

There are definitely games kids shouldn't be playing, she said, for example those where hunting down and killing people is the goal. But she argues that the label "violent video games" is too vague. Researchers need to do a better job at defining what is considered a violent video game and what constitutes aggressive behavior, she added.

"I think there may well be problems with some kinds of violent games for some kinds of kids," Olson said. "We may find things we should be worried about, but right now we don't know enough."

Further, she adds, playing games rated "M" for mature has become "normative behavior" for adolescents, especially boys. "It's just a routine part of what they do," she says.

Her advice to parents? Move the computer and gaming stuff out of kids' rooms and into public spaces in the home, like the living room, so they can keep an eye on what their child is up to.

Dr. David Walsh, president of the National Institute on Media and the Family, a Minneapolis-based non-profit, argues that the pervasiveness of violence in media has led to a "culture of disrespect" in which children get the message that it's acceptable to treat one another rudely and even aggressively.

"It doesn't necessarily mean that because a kid plays a violent video game they're immediately going to go out and beat somebody up," Walsh says. "The real impact is in shaping norms, shaping attitude. As those gradually shift, the differences start to show up in behavior."

Kids shouldn't play games where hunting down and killing people is the goal, says one expert.

Kids in both the U.S. and Japan who reported playing lots of violent video games had more aggressive behavior months later than their peers who did not, according to the study, which appears in the November issue of the journal Pediatrics.

The researchers specifically tried to get to the root of the chicken-or-egg problem -- do children become more aggressive after playing video games or are aggressive kids more attracted to violent videos?

It's a murky -- and controversial -- issue. Many studies have linked violence in TV shows and video games to violent behavior. But when states have tried to keep under-18 kids from playing games rated "M" for mature, the proposed restrictions have often been challenged successfully in court.

In the new study, Dr. Craig A. Anderson, Ph.D., of Iowa State University in Ames, and his colleagues looked at how children and teen's video game habits at one time point related to their behavior three to six months later.

The study included three groups of kids: 181 Japanese students ages 12 to 15; 1,050 Japanese students aged 13 to 18; and 364 U.S. kids ages 9 to 12.

The U.S. children listed their three favorite games and how often they played them. In the younger Japanese group, the researchers looked at how often the children played five different violent video game genres (fighting action, shooting, adventure, among others); in the older group they gauged the violence in the kids' favorite game genres and the time they spent playing them each week.

Japanese children rated their own behavior in terms of physical aggression, such as hitting, kicking or getting into fights with other kids; the U.S. children rated themselves too, but the researchers took into account reports from their peers and teachers as well.

In every group, children who were exposed to more video game violence did become more aggressive over time than their peers who had less exposure. This was true even after the researchers took into account how aggressive the children were at the beginning of the study -- a strong predictor of future bad behavior.

The findings are "pretty good evidence" that violent video games do indeed cause aggressive behavior, says Dr. L. Rowell Huesmann, director of the Research Center for Group Dynamics at the University of Michigan's Institute for Social Research in Ann Arbor.

There are two ways violent media can spur people to violent actions, said Huesmann, who has been studying violence in media and behavior for more than 30 years.

First is imitation; children who watch violence in the media can internalize the message that the world is a hostile place, he explains, and that acting aggressively is an OK way to deal with it.

Also, he says, kids can become desensitized to violence. "When you're exposed to violence day in and day out, it loses its emotional impact on you," Huesmann said. "Once you're emotionally numb to violence, it's much easier to engage in violence."

But Dr. Cheryl K. Olson, co-director of the Center for Mental Health and the Media at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, isn't convinced.

"It's not the violence per se that's the problem, it's the context and goals of the violence," said Olson, citing past research on TV violence and behavior.

There are definitely games kids shouldn't be playing, she said, for example those where hunting down and killing people is the goal. But she argues that the label "violent video games" is too vague. Researchers need to do a better job at defining what is considered a violent video game and what constitutes aggressive behavior, she added.

"I think there may well be problems with some kinds of violent games for some kinds of kids," Olson said. "We may find things we should be worried about, but right now we don't know enough."

Further, she adds, playing games rated "M" for mature has become "normative behavior" for adolescents, especially boys. "It's just a routine part of what they do," she says.

Her advice to parents? Move the computer and gaming stuff out of kids' rooms and into public spaces in the home, like the living room, so they can keep an eye on what their child is up to.

Dr. David Walsh, president of the National Institute on Media and the Family, a Minneapolis-based non-profit, argues that the pervasiveness of violence in media has led to a "culture of disrespect" in which children get the message that it's acceptable to treat one another rudely and even aggressively.

"It doesn't necessarily mean that because a kid plays a violent video game they're immediately going to go out and beat somebody up," Walsh says. "The real impact is in shaping norms, shaping attitude. As those gradually shift, the differences start to show up in behavior."

Taken From an Article written by CNN.com